Concussion is one of the most common injuries to the brain, affecting about two million children and teens every year. It is a particular kind of injury that happens when a blow to the head or somewhere else on the body makes the brain move back and forth within the skull.

It’s possible to get a concussion after what might seem like a minor injury, like a forceful push from behind, or a collision between two players in a football or soccer game.

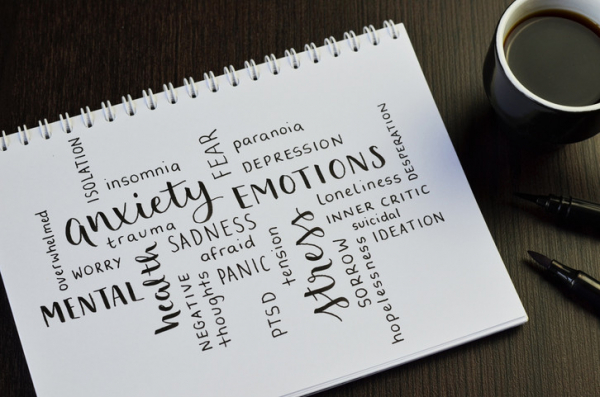

What are the signs and symptoms of concussion?

Because the injury may not seem that significant from the outside, it’s important to know the symptoms of a concussion. There are many different possible symptoms, including

- passing out (this could be a sign of a more serious brain injury)

- headache

- dizziness

- changes in vision

- feeling bothered by light or noise

- confusion or feeling disoriented

- memory problems (such as difficulty remembering details of the injury) or difficulty concentrating

- balance or coordination problems

- mood changes.

Some of these are visible to others and some are felt by the person with the concussion. That’s why it’s important to know the signs and to ask all the right questions of a child who has had an injury.

Sometimes the symptoms might not be apparent right away, but show up in the days following the injury. The CDC’s Heads Up website has lots of great information about how to recognize a concussion.

How can further harm to the brain be avoided?

The main reason it’s important to recognize a possible concussion early is that the worst thing you can do after getting a concussion is get another one. The brain is vulnerable after a concussion; if it is injured again, the symptoms can be longer lasting — or even permanent, as in cases of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a condition that has been seen in football players and others who have repeated head injuries.

If there is a chance that a child has had a concussion during a sports competition, they must stop playing — and get medical attention. It’s important to get medical attention any time there is concern about a possible concussion, both to be sure there isn’t a more serious brain injury, and to do a good assessment of the symptoms, so that they can be monitored over time. There are some screening questionnaires that are used by doctors that can be used again in the days and weeks after the concussion to see how the child is improving.

What helps children recover after a concussion?

Experts have struggled with figuring out how to protect the brain after a concussion. For a long time, the recommendation was to rest and do very little at all. This meant not doing any exercise, not going to school, not even reading or watching television. As symptoms improved, the restrictions were lifted gradually.

Over time, though, research showed that not only was this much rest not necessary, it was counterproductive. It turns out that getting kids back into their daily lives, and back into being active, is safe and leads to quicker recovery. Experts still recommend rest and then moving gradually back into activities, but the guidelines are no longer as strict as they once were.

One important note: A medical professional should guide decisions to move from rest to light activity, and then gradually from there to moderate and then regular activities based on how the child is doing. This step-by-step process may extend for days, weeks, or longer, depending on what the child needs. Parents, coaches, and schools can help support a child or teen as they return to school and return to activities and sports.

Some children will be able to get back into regular activities quickly. But for others it can take weeks or even months. Schools and sports trainers should work with children to support them in their recovery. Some children develop post-concussive syndromes with headache, fatigue, and other symptoms. This is rare but can be very disabling.

How can parents help prevent concussions?

It's not always possible to prevent concussions, but there are things that parents can do:

- Be sure that children use seat belts and other appropriate restraints in the car.

- Have clear safety rules and supervise children when they are playing, especially if they are riding bikes or climbing in trees or on play structures.

- Since at least half of concussions happen during sports, it’s important that teams and coaches follow safety rules. Coaches should teach techniques and skills to avoid dangerous collisions and other injuries. Talk to your child’s coaches about what they are doing to keep players safe. While helmets can prevent many head injuries, they don’t prevent concussions.

About the Author

Claire McCarthy, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing

Claire McCarthy, MD, is a primary care pediatrician at Boston Children’s Hospital, and an assistant professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School. In addition to being a senior faculty editor for Harvard Health Publishing, Dr. McCarthy … See Full Bio View all posts by Claire McCarthy, MD